I tend to obsess over outdoors gear. The pinnacle (or nadir, as the case may be) of this obsession was the spring/summer of 2001, when I hiked the Pacific Crest Trail. Over four months, I sampled a ton of gear — six pairs of shoes, a few different shirts, jackets, socks, shelters, cookware. I had dozens (maybe hundreds) of conversations about this stuff, spent hours discussing the various qualities that distinguished some little piece of backpacking equipment or apparel as the lightest, strongest, driest, most comfortable, most long-lasting, most whatever.What did I take away from these discussions? Two things: (1) At some point, rational evaluation becomes religious debate. Gear nerds have deep, complicated relationships with their hardware, and we have a hard time remaining level-headed about the stuff saves our butt during a thunderstorm, or keeps us consistently comfortable as temperatures change. And, (2), for me, Patagonia apparel lasted longer, bounced back better, fit better, dealt with rain better, and just generally worked better than the other stuff I tried. Others poo-poo-ed it as "Pata-gucci." Froofy, high-end couture posing as outdoor gear, i.e. stuff that "real thru-hikers" wouldn't be caught dead in.All of this is good and well, but I recently came across another excellent aspect of it. (And I still wear it).

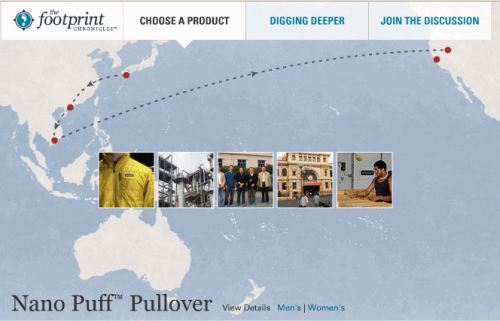

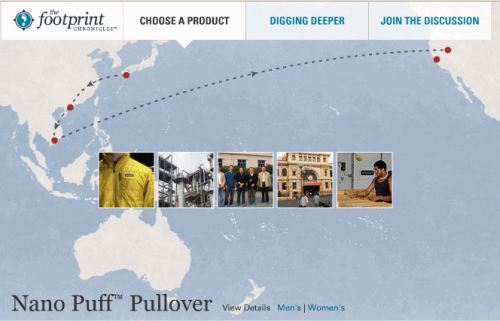

Called the Footprint Chronicles, they're a series of detailed accounts of how individual pieces of their gear are made — where the material is sourced, how fair labor practices are ensured, how the garment is assembled.

Called the Footprint Chronicles, they're a series of detailed accounts of how individual pieces of their gear are made — where the material is sourced, how fair labor practices are ensured, how the garment is assembled. This example takes you through the design and construction of the Nano Puff Pullover, made from recycled polyester.

This example takes you through the design and construction of the Nano Puff Pullover, made from recycled polyester.This is a different kind of marketing, clearly: Documentary accounts that highlight the qualities of the company, rather than the performance of the gear. I'd be interested to know how (or if) they measure the return on investment of this kind of thing.