I love reading, and I've been thinking a lot about how technology is affecting the way that we read now and in the future. I keep thinking about something Sven Birkerts said in a 1998 interview with Harpers: "If you touch all parts of the globe, you can't do that and then turn around and look at your wife in the same way." [PDF] Of course, one could be turn around and look at one's wife in a more informed, more educated way, but that's not the way he sees it. I share this anxiety: I love reading the New York Times on my phone, but I can't help but sense that something will be lost if all printed matter moves in this direction.

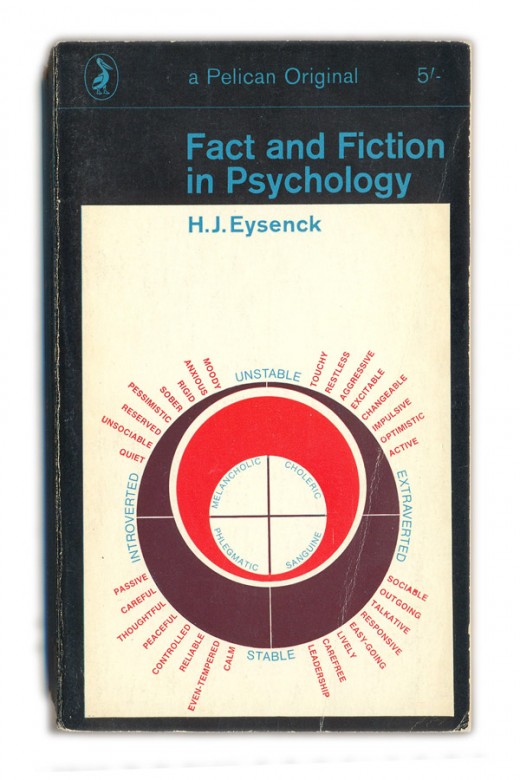

This is the top shelf on one of our book cases. It's comforting to have the books sitting there; they're like a version of myself, sitting on a shelf, disassembled and re-arrangeable.

This is the top shelf on one of our book cases. It's comforting to have the books sitting there; they're like a version of myself, sitting on a shelf, disassembled and re-arrangeable.In August 1995, Harpers Magazine conducted a round table discussion with Wired's Kevin Kelly, author Sven Birkerts, the Well's John Perry Barlow, and Mark Slouka. The results were condensed in the magazine [PDF], and the conversation outlines the two ideologies that continue to converse today: Those who believe that the paper incarnation of the book is an irreplaceable arena for the delivery of its content, and those who don't. Birkerts discusses the former in his 1995 book, The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age. In 2004, the National Endowment for the Arts sent a shot across the bow in a paper called "Reading at Risk," [PDF]. The researchers surveyed 17,000 people, and they concluded that the future of literary reading is bleak: "Literary reading in America is not only declining rapidly among all groups, but the rate of decline has accelerated, especially among the young."Still, the total number of books sold continues to rise, so is the future really that bleak? The NEA thinks so. It released a follow-on to Reading at Risk called "To Read or Not To Read." This study focuses on young readers, and links the decline in reading to "civic, social and economic" risks.Last spring, Nicholas Carr discussed Google's effect on literary reading in the Atlantic, provocatively titled "Is Google Making Us Stupid." [I discussed this in a blog post at the Cooper Journal called "Dumb is the new smart"]. In it, he interviews a blogger who confesses the following:

"I can't read War and Peace anymore,†he admitted. "I've lost the ability to do that. Even a blog post of more than three or four paragraphs is too much to absorb. I skim it."

The article also sparked a discussion on brittanica.com, collected in a forum called "Your Brain Online." It's got a lot of interesting stuff from folks like Kevin Kelly, Danny Hillis and Clay Shirky, author of Here Comes Everybody, who thinks that the "unprecedented abundance" of the web will function to break the vise-grip of the "literary world" on culture:

It's not just because of the web — no one reads War and Peace. It's too long, and not so interesting. This observation is no less sacrilegious for being true. The reading public has increasingly decided that Tolstoy's sacred work isn't actually worth the time it takes to read it, but that process started long before the internet became mainstream … The threat isn't that people will stop reading War and Peace. That day is long since past. The threat is that people will stop genuflecting to the idea of reading War and Peace.

Ursula Le Guin disputes the notion that people have ever read War and Peace. (Well, maybe.)

Self-satisfaction with the inability to remain conscious when faced with printed matter seems questionable. But I also want to question the assumption — whether gloomy or faintly gloating — that books are on the way out. I think they're here to stay. It's just that not all that many people ever did read them. Why should we think everybody ought to now?

The title of her recent Harper's essay pretty well sums up her position: "Notes on the alleged decline of reading." It roars through the various aspects of the state of reading and publishing, quickly turning into a ringing indictment of corporate publishers:

The social quality of literature is still visible in the popularity of bestsellers. Publishers get away with making boring, baloney-mill novels into bestsellers via mere P.R. because people need bestsellers. It is not a literary need. It is a social need. We want books everybody is reading (and nobody finishes) so we can talk about them.

On that social note

I was just looking at my beat-up copy of "The Dharma Bums," and I felt a sort Chris Matthews-esque tingle. I bought it during high school at Rainy Day Books in Fairway, Kansas, and it sparked my fascination with the West Coast, years before I ever traveled here. Would I ever read it again? Probably not. In fact, just now, I could barely read even a couple of pages without feeling like Kerouac was on auto-pilot. But I like the idea that my bookshelf is a kind of externalization of myself, a collection of important influences and expressions. The future of my books appears to be not so different than the present: A combination of talismans, objects of beauty, and points of reference.On the subject of reference, in (wait for it) a Harper's essay called ""A Defense of the Book," William Gass talks about the pleasures of not having the world at your fingertips:

I have rarely paged through one of my dictionaries (a decent household will have a dozen) without my eye lighting, along the way, on words more beautiful than a found fall leaf, on definitions odder than any uncle, on grotesques like gonadotropin-releasing hormone or, barely, above it — what? — gombeen — which turns out to be Irish for usury.

And holy crap, there's a whole lot more Gass at Tunneling. Articles, links, thoughts. I love the Internet.

This is the top shelf on one of our book cases. It's comforting to have the books sitting there; they're like a version of myself, sitting on a shelf, disassembled and re-arrangeable.

This is the top shelf on one of our book cases. It's comforting to have the books sitting there; they're like a version of myself, sitting on a shelf, disassembled and re-arrangeable.