New York's blizzard of 1977 makes a riveting cameo appearance in "El Super," an indie (before the term was formalized) film about the hard adjustments that immigrants make in coming to New York. The movie is great for many reasons, but the blizzard steals a few scenes as the main character — a Cuban super — walks around town. Snow is massed on cars, piled high in the streets, and pedestrians stumble through snow-walled sidewalk canyons. Quite a scene, especially in the 70s, when New York looked crumbly and decrepit.Amidst the blizzard, the film is a melancholy document of the lives of Cuban and Puerto Rican immigrants as they reckon with the immensity of New York City and their dismal prospects for work in the bad old days of New York. The dialogue is great, often funny, just as often poignant. Good stuff. I had to resort to extreme measures to find it, but you can buy it on VHS from Amazon. Or you can let me know, and I'll hook you up.Speaking of the blizzard, you may have wondered whether Barney Miller ever dealt with the blizzard. Of course he did. Worth watching just to hear the theme song again.

Tag: new yorker

Even though I'm generally a West Coast kind of guy, I devour books about New York — its chaotic beginnings as a lawless, crazy quilt of neighborhoods and gangs; its transformation into a massive modern city; the peculiar dynamics of its organic growth. If New York didn't destroy me everytime I visit, I think I'd probably live there.A few weeks ago, the New Yorker's Twitter stream pointed me to an excellent Joseph Mitchell essay about a (mostly) vanished New York tradition, the beefsteak. Mitchell laid out the basics in his classic 1939 essay, "All You Can Hold For Five Bucks:"

The foundation of a good beefsteak is an overflowing amount of meat and beer. The tickets usually cost five bucks, and the rule is "All you can hold for five bucks." If you're able to hold a little more when you start home, you haven't been to a beefsteak, you've been to a banquet that they called a beefsteak. From Up in the Old Hotel, an amazing collection of Mitchell's New Yorker essays

We've missed out on the beefsteak's prime, so to speak, but the Beacon Restaurant started a new tradition 10 years ago. The New York Sun's account of the 2004 edition includes courses very much like those Mitchell describes — tiny hamburgers, bacon-wrapped lamb kidneys, double-thick lamb chops, and of course steak — "huge roasted Certified Angus shell loins that had been cut into thick slabs and doused with melted butter."This year's beefsteak is in February. I'm intrigued, though I'm sure it will destroy me.

The man of steal

Baseball great Rickey Henderson recently gave the Hall of Fame induction speech to end all induction speeches. He was a larger-than-life figure in my childhood, and he had a personality to match, often referring to himself in the third person. For example, "There are pieces of this puzzle that Rickey is still working out," in a discussion of age and baseball in an excellent New Yorker profile. There was no third-person in the speech, but there was plenty of Rickey being Rickey:

As a kid growing up in Oakland, my heroes were Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Reggie Jackson. What about that Reggie Jackson? I stand outside the ballpark in the parking lot, waiting for Reggie Jackson to give me an autograph … I said, 'Reggie, can I have an autograph.' He would pass me a pen, with his name on it.

The best part is that Jackson is sitting behind him, cracking up, along with Robin Yount and various other living legends. You can watch the whole thing, in three parts, on YouTube: Part 1 has some awesome commentary by Tony Gwynn and Torii Hunter; Part 2 is the beginning of Rickey's speech; Part 3 is the conclusion.

These are our core beliefs

What I know about the inner-workings of politics I learned in The Power Broker, and therefore I don't claim to know much other than the sausage-making involved in building the Triborough Bridge. Still, I was struck by the following passage from Ryan Lizza's New Yorker profile of Peter Orszag, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget.

The first budget, [Robert Nabors, an OMB veteran] told me, "was being designed with an eye toward what do we need to do to put the economy back on a more sustainable path? What do we need for economic growth? And what do we need to do in order to transform the country? Those were our overarching principles." The budgeteers took a hyper-rational approach, attempting to determine policy and leave the politics and spin for later. He went on, "One of the things that would probably surprise people is that this wasn't an effort where anybody created a top-line budget number and said, 'This is the number that we have to hit, and that's just that, and we'll fit everything else in.' Or, 'We can't go higher than x on revenue,' or, 'We can't go higher than y on spending.' It was more of a functional budget than anything else: 'This is what we need to do. These are our principles. These are our core beliefs. And as a result this is what our budget looks like.'"

This is probably the kind of thing that gives nightmares to the teabaggers, but I love the idea of goal-oriented budget creation. Why not try to keep your eyes on the prize of actual tangible outcomes like sustainble economic growth when you're wrangling the world's most complicated spreadsheet into submission?

Last night I read the New Yorker profile of Matthew and Michael Dickman, poets from Portland, Oregon who happen to be identical twins. (Here's the abstract). In their work, they have very different voices, but there's a strange sort of twin telepathy that seems to exist within it. They also edit each other's work, providing insight and feedback to each other about works in progress. During one editing session, one of the Dickmans recalls an interview with former American poet laureate Mark Strand in which Strand cautions against relying on "clusters of words" that pop into your head … This sounded to me like a good rule of thumb for writing. (It also added fuel to the fire of my dislike of Twitter and Twitter-like tools that encourage people to offer half-cocked, cliche-ridden mini-opinions about everything.) I plundered the Internet in search of the interview. Turns out that he was referring to a 2003 piece in Post Road Magazine. It was conducted by writer Michael O'Keefe. The relevant bit is the last passage from Strand, but the context is helpful:

Mark Strand: Nobody wants to arrive because that's the end. One wants to have openings constantly before him so there are places to go.Michael O'Keefe: Do you believe that sometimes words can get in the way when you write?MS: Words do get in the way when you have heard them used in a particular manner before. When you write all you've got are words but they both get in the way and serve as a salvation.MO: Do you avoid using any kind of combinations of words that you could remember easily?MS: Yeah, I mistrust them because it means that they existed in that way before. The idea is to use a modifier-noun combination that may never have been used before. Otherwise you may be just quoting others or quoting yourself. The excitement comes when you have done something that was unthinkable before.

Amen, brother. Mistrust ease. Seek the unthinkable.In my digging, I also found some excellent Strand resources, including a nice interview in a 1975 issue of Ploughshares and a very helpful page at the Library of Congress that eventually led to my discovery of the above interview.

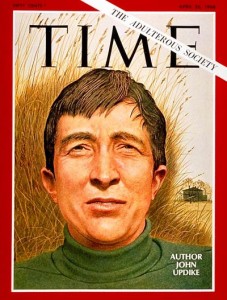

Updike

I love writing letters, but for some reason the only letter-to-the-editor I've ever written went something like this:

Dear Mr. Remnick, If you publish one more story by John Updike, so help me God I will cancel my subscription immediately.Sincerely, Doug LeMoine

The year was 1999. I had been driven to what I saw as the brink — of patience! of sanity! — by the New Yorker's incessant publishing of Updike's fiction, which seemed (to me) not only incessant, but over-stylized, nauseatingly East Coast-ish, maudlin, wooden. No matter my mood, I found it insufferable and insulting, tone-deaf when it came to anything but older white guys. I don't like to speak ill of the departed, so I'll stop there and I'll admit that I've softened in the meantime. Updike's literary criticism is — who can argue? — instructive and insightful. He knew his stuff, and I felt enriched (sometimes grudgingly so) when I read his reviews. With regard to the aforementioned letter, my hand was forced almost immediately. Updike had published something like 25,000 stories in the New Yorker to that point, so I might as well have told John Henry to stop driving steel, or for Jerry Garcia to stop jamming. By the time my letter was fluttering into David Remnick's trashcan, I was already being forced to make good on my threat, a task that was ultimately embarrassing in its cold, bureaucratic execution. Contrary to any engaged reader's conception of the publisher-reader relationship, when you say "I'd like to cancel my subscription," they don't transfer you to the desk of the editor so that you can ream him a new one. You hear a few keystrokes, and then get asked if there's anything else you need help with. Upon reflection, this experience was a life lesson in itself. Mr. Updike, I thank you, and I wish you well.

(The title is from a poet named Tao Lin in a collection called this emotion was a little e‑book).The Internet is like a small town, especially when there's something to disagree about. Recently, some of my favorite Internet citizens got into it over Obama's decision to have poetry at his inauguration.I've always liked George Packer, the New Yorker's man on the ground in the early days of Iraq. I devoured his book about the first year of the occupation, The Assassins' Gate. It tells the stories of a few Iraqis who put their necks on the line to support us when we arrived in 2003, and it comes to mind whenever a conversation turns to the need to find a way out of Iraq. I also read his blog, Interesting Times. He's the kind of journalist who always does his homework, which made it all the more puzzling when he somewhat flippantly criticized Barack Obama's decision to ask Elizabeth Alexander to read a poem at his inauguration:

For many decades American poetry has been a private activity, written by few people and read by few people, lacking the language, rhythm, emotion, and thought that could move large numbers of people in large public settings … [Ed.: Ouch.] … Obama's Inauguration needs no heightening. It'll be its own history, its own poetry.

Ouch. A blanket dismissal? The activity of "a few people?" I started writing a response to this, but Ta-Nehisi Coates of The Atlantic beat me to it. His blog rules. He called out Packer for being prematurely judgmental, and suggested that perhaps hip-hop lyrics were suitably rhythmic and emotive for the occasion. Yes.Lo and behold, Packer just posted what amounts to an apology, and he does so in the best way, comparing the current poetry scene to the NBA in the 1970s:

Contemporary American poetry has too many mansions to be summed up under a throwaway phrase like "private activity.†Its multitude of schools and forms is like the N.B.A. in the nineteen-seventies, when there was no dominant team but a confused contest of warring tribes. And I should have read more of Alexander's work than appears on her Web site, and more carefully, before expressing skepticism that she'll be equal to the occasion on January 20th.

So, the real question is: Who will be the David Stern of 21st century American poetry? Chris Fischbach, I'm looking at you.