My nomination for All-Time Best Moment In An Art Documentary has to be the "Bullshit!" scene in Concert Of Wills: Making The Getty Center. Abstract-artist-turned-landscape-designer Robert Irwin literally calls bullshit on architect Richard Meier during an important Getty Center planning session. [The object of their disagreement is Irwin's garden design, pictured at right. Thx, brewbooks.] Design Observer's Michael Bierut sums it up nicely in an article called "On (Design) Bullshit:"

The [Getty Foundation], against Meier's advice, has brought in artist Robert Irwin to create the Center's central garden. The filmmakers are there to record the unveiling of Irwin's proposal, and Meier's distaste is evident. The artist's bias for whimsical organic forms, his disregard for the architecture's rigorous orthonography, and perhaps even his Detroit Tigers baseball hat all rub Richard Meier the wrong way, and he and his team of architects begin a reasoned, strongly-felt critique of the proposed plan. Irwin, sensing (correctly, as it turns out) that he has the client in his pocket, listens patiently and then says, "You want my response?"His response is the worst accusation you can lodge against a designer: "Bullshit."

If I recall correctly, Meier is speechless, and the mood of the documentary shifts quite significantly. Meier's personality and viewpoint had dominated (is "domineered" a word?) earlier scenes, he maintains a sort of icy distance in subsequent scenes. (Disclosure: While I respect Meier, I'm not a fan of his work, especially the Getty, and the documentary makes clear that he is, umm, a dick). Irwin, on the other hand, I've always loved, especially his dot paintings. I'm currently reading Lawrence Weschsler's biography of Irwin, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, and it contains some useful background and context to the "Bullshit!" scene. It also complicates it; the more I read, the more Irwin and Meier seem to have quite a lot in common. I'd always assumed that Irwin's vision was the irrational, organic counterpoint to Meier's rational, geometric forms. The book makes clear that Irwin has quite a lot of the rational geometry on the brain himself. Perhaps they were just too similar to get along.A large portion of the book is dedicated to Irwin's discussion of his own process … My favorite passage involves Irwin's explanations of the fits and starts that characterized his output, especially during the dot painting phase:

"Most of the time, I didn't have any idea where it was going; I had no intellectual clarity as to what it was I thought I was doing … Maybe I was just gradually developing a trust in the act itself, that somehow, if it were pursued legitimately, the questions it would raise would be legitimate and the answers would have to exist somewhere, would be worth pursuing, and would be of consequence."Actually, during those years in the midsixties," he doubled back on his formulation, "the answers seemed to matter less and less: I was becoming much more of a question person than an answer person … The thing that really struck me as I got into developing my interest in the area of questions," Irwin continued, "is the degree to which as a culture we are geared for just the opposite. We are past-minded, in the sense that all of our systems of measure are developed and in a sense dependent upon a kind of physical resolution. We tag our renaissances at the highest level of performance, whereas it's fairly clear to me that once the question is raised, the performance is somewhat inevitable, almost just a mopping-up operation, merely a matter of time."

This is a photomontage by a Polish artist named Janusz Maria Brzeski. It's called Twentieth-Century Idyll, but the name of the series is even better: A Robot Is Born. Photo: National Gallery of Art.

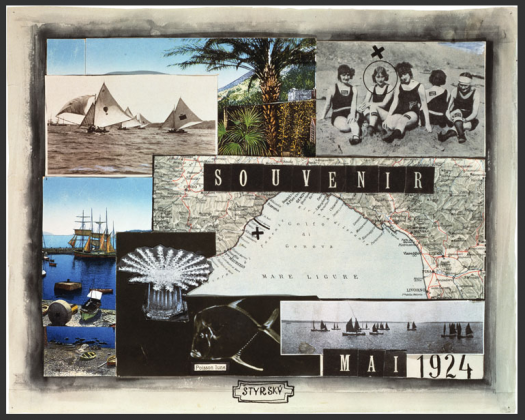

This is a photomontage by a Polish artist named Janusz Maria Brzeski. It's called Twentieth-Century Idyll, but the name of the series is even better: A Robot Is Born. Photo: National Gallery of Art. Another photomontage, this one by Jindrich Strysky, a Czech artist. Photo: National Gallery of Art

Another photomontage, this one by Jindrich Strysky, a Czech artist. Photo: National Gallery of Art A moment from a beautiful, riveting scene in

A moment from a beautiful, riveting scene in  No dialogue. Dog mask. Chain link fence.

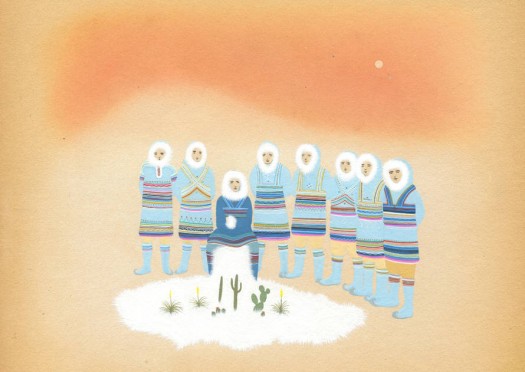

No dialogue. Dog mask. Chain link fence.  Rachell Sumpter, Argonauts. From her collection at the

Rachell Sumpter, Argonauts. From her collection at the