This is a photo by Thomas Allen. I first noticed his stuff when I saw the covers of Vintage reissues of James Ellroy's novels (like this one for Suicide Hill). The photo above is from a series of dioramas that Allen created from cut-outs of 50's pulp novels. I love the use of the book-ends as textured underwater scenery here. Genius. Photo: Foley Gallery.

A lot of what I've been reading seems to resonate with my 9‑to‑5 work. Last night, I was reading architect Witold Rybczynski's account of a shed-building exercise that turns into a much, much more — The Most Beautiful House in the World, and this passage jumped out at me, mostly because it spoke so eloquently of the stuff I value in design work:

The psychologist Bruno Bettelheim once characterized children's play as an activity "characterized by freedom from all but personally imposed rules (which are changed at will), by free-wheeling fantasy involvement, and by absence of any goals outside the activity itself" …

Bettelheim quotes a four year-old who asks, "Is this a fun game or a winning game?" The solitary building game is a fun game–there is no opponent. The concept of fun is elusive and resists easy definition, but it is an undisputed element–perhaps the element–of play. In the present context, it is enough to note that fun does not imply folly or lack of seriousness–quite the opposite … What keeps [the architect] involved for such long periods of time is that the outcome of the design process is unpredictable: it is the result of chance, as in play. He does not know ahead of time exactly what the result will be. He could save himself a lot of time and look for a similar building to reproduce exactly; but this would make as little sense as building the same house of cards again and again, or solving the same crossword puzzle. The issue here is not originality but fun.

The emphasis in that paragraph is mine. This weekend, I was reading a New York Times feature on my man Robert Irwin, and I found myself smiling at this:

A favorite term is "participation." [Irwin] cites, for example, his 1997 transformation of a room that overlooks the Pacific at the La Jolla branch of the San Diego museum. Reasoning that he could not compete with the sweeping view, Mr. Irwin cut three rectangles — squares almost — into the existing windows. "At first I didn't realize the glass was tinted," he said. "So not only did my holes let in air and sound, adding another dimension to the experience, but they made everything seen through them appear in greater focus." You might say he opened the window, that age-old pictorial device, letting in a cool rush of reality.

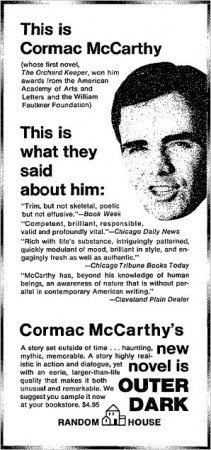

Once upon a time, I wrote a long post about Irwin's biography, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees by Lawrence Wechsler; when I say that it blew my mind, I mean that the book expanded my mind, made me really think about the way I recognize, interpret and understand the things I see. Finally: Cormac McCarthy. I'm reaching back in time, back to 1994, back to the night I disgustedly flung my copy of All the Pretty Horses out the window of my apartment. (Later that night, I saw the same copy for sale at 16th and Mission BART). Anyway, I'm willing to reconsider my judgment that McCarthy is no more than a smartypants Zane Grey writing for armchair gauchos. The Road stuck with me, really deeply upset me, and I respect that. So I'm giving him another try, and so far, so good: I got a nice copy of The Border Trilogy, and was quickly transported by the prose, though of course I was reminded of Owen Wilson's character Eli Cash, in The Royal Tenanbaums. His book, Old Custer, was written in what he characterized as an "obsolete vernacular," exhibited in this excellent bit:

The crickets and the rust-beetles scuttled among the nettles of the sage thicket. "Vámonos, amigos," he whispered, and threw the busted leather flintcraw over the loose weave of the saddlecock. And they rode on in the friscalating dusklight. [More quotes from the Royal Tenanbaums]

Damn, that's good.