Category: california

Only worn when mobbin'

So I was catching up with the haps in my new city today on Berkeleyside, and I noticed a reference to yet another cool thing that originated in Oakland. No, it's not turf dancing, or whistle tips, or ghost riding, or even hyphy. It's scraperbikes, old beaters totally tricked out with colorful, cheap, homespun decorations. Not only are they cool-looking, the scraper crew wrote some by-laws to keep it all legit:

In order to become a member of the Original Scraper Bike Team, you must: Be a resident of Oakland, CA. Be at least 7y/o or older. Retain A 3.0 Grade Point Average (GPA), Create your own Scraper Bike…(It Has To Be Amazing, Or Else You Can't Ride.) A single-file line when riding. After 10 rides The Scraper Bike King and his Captains will decide if your bike is up to standards and if you can follow simple guidelines. After your evaluation we will consider you a member and honor you with an Original Scraper Bike Team Shirt. Only worn when Mobbin'.

The above quote, and the still are from a beautiful short movie called Scrapertown by Zackary Canepari & Drea Cooper, which you should definitely watch for the sheer awesome camerawork alone. They have a series of lovely videos about California called California is a place, also worth checking out.

Cycling seems more dangerous, more hassle-filled, and generally more aggro than when I moved here. Why? Maybe it's me. I moved to Berkeley recently, and I'm pretty close to having a lawn that I can tell kids to get off of. Maybe it's that the city has changed a lot. There are more cyclists, more people in general (60,000!) and more density, especially downtown. On the other hand, there are more bike lanes and signage, and there's more bike awareness among the pedestrian and motorist populations. You'd think that more cyclists + more cycling awareness + more cycling accommodation would have resulted in some kind of net improvement, but it hasn't. Pedestrians seem more antagonistic to bikes; motorists of all types are much more antagonistic; and some of my fellow cyclists seem to be the most antagonistic of all. Why?Felix Salmon has written a really interesting, and widely quoted, "unified theory" of cycling that touches on what I think is the heart of it all: That most cyclists think they're pedestrians, when we're actually more like motorists.

Bikes can and should behave much more like cars than pedestrians. They should ride on the road, not the sidewalk. They should stop at lights, and pedestrians should be able to trust them to do so. They should use lights at night. And — of course, duh — they should ride in the right direction on one-way streets. None of this is a question of being polite; it's the law. But in stark contrast to motorists, nearly all of whom follow nearly all the rules, most cyclists seem to treat the rules of the road as strictly optional. They're still in the human-powered mindset of pedestrians, who feel pretty much completely unconstrained by rules.

I really agree with this. I don't know how to make it so, and I'm really not a law-and-order type. But I think that agreeing to follow the rules of the road would do a lot to make us all more predictable. Also, I'd like to add: Pass on the freakin left.

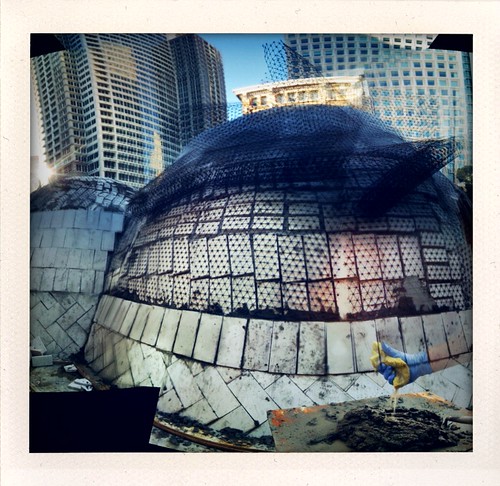

My old friend Michael Ramage has a hand in this installation in the Yerba Buena Center for Art's Sculpture Garden. He's designing and building a pair of domes, made from layers of bricks and mortar and styled on ancient techniques. The artist behind it is Jewlia Eisenberg & Charming Hostess, and the vision is that the domes will be an outdoor venue for music, contemplation, and mind-expanding activities throughout the summer. I visited on Tuesday, and I was struck by the ways that each dome's oculus (fancy word for the open, circular window at the top of the dome) framed the surrounding sky and buildings. That perspective actually kind of made the generic buildings at 3rd and Howard appear to be somewhat cool. Didn't think that would be possible.

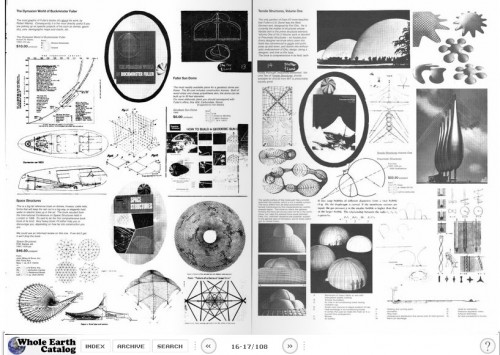

When the Whole Earth Catalog (WEC) was published in late 60s and early 70s, the idea was to create a finely curated list of everything "useful, relevant to independent education, high quality or low cost, not already common knowledge, and easily available by mail."

The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, Fall 1968. From Arts & Ecology.

The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, Fall 1968. From Arts & Ecology.Steve Jobs once referred to the WEC as "the bible" of his generation, and it's no wonder that he admired it: Each issue of the catalog was sprawling, ambitious, smart, lovingly crafted, and very much in keeping with the best of Northern California's innovative spirit — progressive, irreverent, and (in its own way) ruthless.The title of this post refers to a (perhaps apocryphal) account of the user experience considerations of the WEC. Reportedly, the catalog's design editor, J. Baldwin, said that the catalog was an attempt to bring everything (of value) in the world to within two1 phone calls for any reader. Which was undoubtedly great at the time, but not quite good enough to escape the development of the one-call solution — the dial-up modem. Doh! And the no-call solution — broadband!And yet, when you compare the infinite variety of the web to the refined encapsulation of the WEC, it's easy to see the value of expert curation. Doesn't it seem like the great opportunities for progress in web content is to become more like the WEC — reliable, readable, smart? And even reader-supported? (After all, the WEC cost $5 in the 60s; $31.85 today. As one of the Whole Earth editors wrote, people will pay for authenticity and findability).1 For the record, I'm not exactly sure what the significance of "two" is, rather than "six" or "three." Would the first call would be the Whole Earth Catalog, and the second would be to … the product creator? Or the first would be to the product creator, and the second would be to … someone else?

In a cloud

Oh wow, our pal Greg Gardner put together a really nice collection of new music from local bands. It's called In A Cloud, which describes the recent winter weather and the album itself is a time capsule of San Francisco sounds in 2009-10. My favorite song is a sweet little thing called "Baby Held" by the elusive and pseudonymous Jacques Butters; you can listen to it below. There's plenty more on the album — a lovely track by Sonny & the Sunsets, a good one from the Sandwitches, a keeper from Kelley Stoltz. You can buy it directly from Greg's label, Secret Seven Records. Yay.

I tend to obsess over outdoors gear. The pinnacle (or nadir, as the case may be) of this obsession was the spring/summer of 2001, when I hiked the Pacific Crest Trail. Over four months, I sampled a ton of gear — six pairs of shoes, a few different shirts, jackets, socks, shelters, cookware. I had dozens (maybe hundreds) of conversations about this stuff, spent hours discussing the various qualities that distinguished some little piece of backpacking equipment or apparel as the lightest, strongest, driest, most comfortable, most long-lasting, most whatever.What did I take away from these discussions? Two things: (1) At some point, rational evaluation becomes religious debate. Gear nerds have deep, complicated relationships with their hardware, and we have a hard time remaining level-headed about the stuff saves our butt during a thunderstorm, or keeps us consistently comfortable as temperatures change. And, (2), for me, Patagonia apparel lasted longer, bounced back better, fit better, dealt with rain better, and just generally worked better than the other stuff I tried. Others poo-poo-ed it as "Pata-gucci." Froofy, high-end couture posing as outdoor gear, i.e. stuff that "real thru-hikers" wouldn't be caught dead in.All of this is good and well, but I recently came across another excellent aspect of it. (And I still wear it).

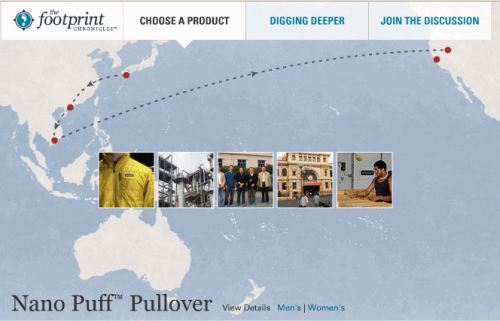

Called the Footprint Chronicles, they're a series of detailed accounts of how individual pieces of their gear are made — where the material is sourced, how fair labor practices are ensured, how the garment is assembled.

Called the Footprint Chronicles, they're a series of detailed accounts of how individual pieces of their gear are made — where the material is sourced, how fair labor practices are ensured, how the garment is assembled. This example takes you through the design and construction of the Nano Puff Pullover, made from recycled polyester.

This example takes you through the design and construction of the Nano Puff Pullover, made from recycled polyester.This is a different kind of marketing, clearly: Documentary accounts that highlight the qualities of the company, rather than the performance of the gear. I'd be interested to know how (or if) they measure the return on investment of this kind of thing.

Days of old (growth)

Sarah brought over an excellent old book called The Trees of California, by Willis Linn Jepson. It was published in 1909, and it had some amazing photos of the redwoods up north.

The caption reads: "Fig 15. REDWOOD (Sequoia sempervirens Endl.) Making the "undercut", which determines the direction of the fall, on a tree 16 feet in diameter. Humboldt woods." Photo: A.W. Ericson.Amazon sells Trees of California for $75, but you can read it for free at Google Books. Cool.

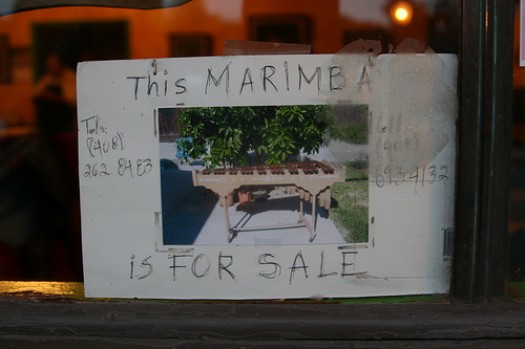

This marimba could be yours

If you haven't been to San Juan Bautista, you need to go. It's a little ways south of San Jose, an hour east of Big Sur, a long but not impossible trip from San Francisco. Mara and I were there last winter, and I keep meaning to spread the word. It's a real getaway with good old-fashioned California heritage and big cacti and a nice bakery and a good vibe.

It's also got a mission, and it's in the heart of artichoke country. They say that hard times are when the big ideas really take hold. Maybe it's time to get that marimba you've always wanted.

Last Friday, we improvised a parlor game during a visit to Sarah's parents’ house. They've got tons of books on California history, including a gem called California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names by one Erwin Gudde, a Cal professor and friend of Sarah's fam. There wasn't much "game" to the game; someone shouted out a city or county or river name, and then we all offered theories about its origin before flipping to its entry in the book and reading aloud. A sample. Yosemite:

From the Southern Sierra Miwok yohhe' meti or yosse' meti [meaning] "they are killers," derived from yoohu- [meaning] "to kill," evidently a name given to the Indians of the valley by those outside it … Edwin Sherman claimed discovery of the valley in the spring of 1850, naming it "The Devil's Cellar." In March of 1851, it was entered by the Mariposa Battalion and named at the suggestion of LH Bunnell: "I then proposed that we give the valley the name of Yo-sem-i-ty, as it was suggestive, euphonious, and certainly American; that by so doing, the name of the tribe of Indians which we met leaving their homes in this valley, perhaps never to return, would be perpetuated."

There's so much information in here that it's hard to know where to start, but (1) Yes, majestic wilderness should be called things like "they are killers." This should be a requirement for any place that is rugged and majestic and awe-inspiring. What words can match landscapes like these? Those that involve violent death, for starters. (2) I can guess at why were the Indians leaving, "perhaps never to return," but this seems like a detail that should be, say, expanded. (3) The "y" at the end, for my money, makes more sense. It was replaced by an "e" in 1852 by a Lt. Tredwell Moore. No explanation is given as to why; the implication is, why not? More on Yosemite here, but the whole book is pretty great.