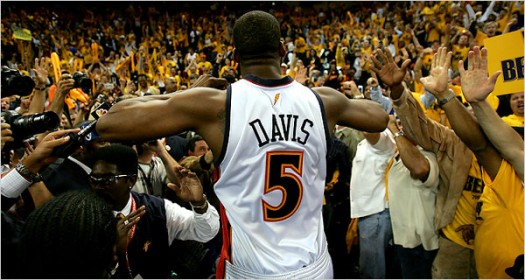

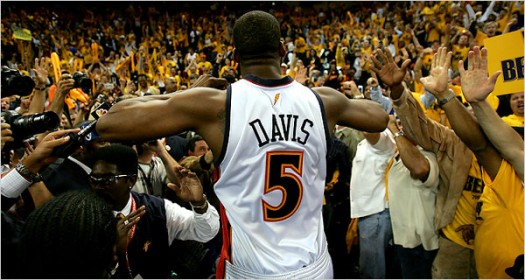

The Bay Area: Where Baron happens. Photo: Jed Jacobsohn/Getty Images

The Bay Area: Where Baron happens. Photo: Jed Jacobsohn/Getty ImagesLiving in the Bay Area, I've watched Baron Davis and Don Nelson breathe life into the corpse of the Golden State Warriors by playing fast, loose, undisciplined, unpredictable basketball. When they're clicking, the Warriors are invigorating and life-affirming. Nellie doesn't burden the team with structure — they don't really run an "offense" or play "defense" in the traditional senses — instead, they rely on the players' abilities to improvise, pull their opponents out of their own structures, and wear them down with running and gunning.

Playground electicity

When the Warriors are good, they're like the best playground basketball team you could ever imagine. What makes them all the more exciting is that their roster lacks key traditional dimensions associated with successful teams. They compete without the traditional man-mountain in the low-post to take on Shaq, Yao, Duncan, or Pau; instead, Andris Biedrins, who has very little in the way of a J and doesn't ever try to play facing the basket, uses his quickness and hops to rebound, follow, and generally surprise opponents with his ability to keep Warrior possessions alive. (Check out where The Wages of Wins ranked Biedrins for the 2006–2007 season) Spoiler: He's #1 on the team, with 11.7 to Baron's 9.7. On the guard front, Baron and Stephen Jackson and Monta Ellis don't really run an offense as much as they weave through defenses in perpetual one-on-fives, driving to the rim, dishing to teammates. Baron has a (admittedly deserved) reputation as a shoot-first point guard, but he defers to others when they're hot and his teammates seem to feed off his energy. Monta, more of a two-guard than a point, somehow can't shoot the three, but he can blow by just about anyone and he's one of the better finishers in the league right now. 6'9" Al Harrington is more reliable from behind the arc than he is with his back to the basket; Wages of Wins doesn't think much of him, but it's hard to deny the problems that he creates for defenses when he's in the game. Stephen Jackson — Stack Jack, as Baron calls him — is the glue; when he's in the game, everyone is better. Seriously, who wouldn't want to play with him? He's got everyone's back.

Darnell can't do it alone. Photo: Nick Krug, Lawrence Journal-World.

Darnell can't do it alone. Photo: Nick Krug, Lawrence Journal-World.Contrast the Warriors with the other team that I follow, the Kansas Jayhawks. Where the Warriors are dangerous, inscrutable, fierce competitors who save their best for big games, the Jayhawks have been the opposite: soft, predictable, vulnerable when the game is on the line. Where the Warriors have at least three guys who thrive in pressure situations — Baron, Stack Jack, and Harrington — the Jayhawks have eight guys who could start on any team in America, but not one who wants to take over a game. Last week, I trekked to Oracle with Justin, Mara, and Lynne (Lynne? Blog?), and we watched the Warriors wear down the Celtics and, in the final moments, drive a dagger into their hearts. Three days later, I watched the Jayhawks wilt in the final moments against a very, very fired up Oklahoma State team. Part of the problem is that Kansas simply doesn't have reliable offensive weapons; another part is that teams love beating the Hawks, and each Jayhawk opponent is playing its biggest game of the season. College basketball is different in that regard. Message boards don't rejoice each time the Lakers lose a game, but oh how people love to see teams like Kansas (Google: "kansas" + "choke"), Duke (Google: "duke" + "choke"), and Kentucky (Google: "kentucky" + "choke") lose. Which is fine. If people didn't really react this way, the wins wouldn't be as much fun.The root of the Hawks' problem is offensive, though. The Warriors are stocked with guys who can create their own shot, but Kansas has to rely on Mario Chalmers and Sherron Collins (and, to some extent, Russell Robinson) to break down defenses and spring Brandon Rush on the perimeter or Darrell Arthur inside. Like the Warriors, the Hawks don't run a structured offense with interchangeable parts; they rely on athleticism. This lack of dimension is easily exploited by teams who effectively pressure the Hawks' guards, and who run big guys out to trap the ball at the three-point line. Add to this mix the fact that Kansas guards cannot seem to defend opposing guards, and there's no question that they've got some big problems to solve before mid-March.

This is closest I could come to a shot of the bench at that moment Mario's shot goes through the net. It's unclear who it is from this photo, but it's almost certainly the same guy you can see onscreen, jumping and celebrating.

This is closest I could come to a shot of the bench at that moment Mario's shot goes through the net. It's unclear who it is from this photo, but it's almost certainly the same guy you can see onscreen, jumping and celebrating.

Darnell can't do it alone. Photo:

Darnell can't do it alone. Photo: